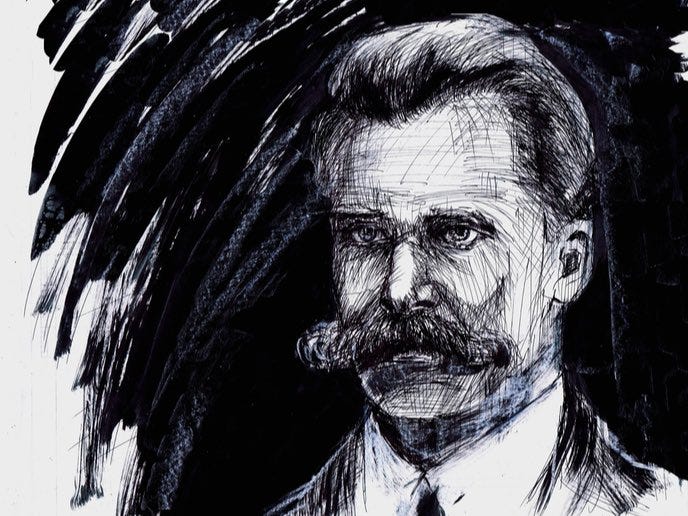

Nietzsche and His Century — Oswald Spengler

Speech by Oswald Spengler delivered on October 15, 1924, on the 80th birthday of Nietzsche, at the Nietzsche Archive in Weimar

Whoever looks back at the 19th century today and lets its great figures pass by finds something astonishing in the figure of Nietzsche, something his own time could hardly have felt. All the others, even Wagner, Strindberg, and Tolstoy, somehow carried the color and form of those years. They were somehow bound to the flat optimism of their progress philistines, their utilitarian and social ethics, their worldview of power and material, adaptation and expediency, and made countless sacrifices to the spirit of the age. Only one person makes a ruthless exception from this, and if the word "untimely," which he himself coined, can still apply to anyone today, it was Nietzsche himself. For in his entire life and the entirety of his thinking, one will search in vain for anything where he inwardly succumbed to a fashion.

He thus stands in contrast and yet also in a deep inner kinship with the second German of modern times, whose life was a great symbol: Goethe. They are the only two distinguished Germans whose existence has depth beyond and alongside their works, and because both felt so from the beginning and constantly accounted for it, their lives have become common property of their nation and an essential part of its intellectual history.

But it was Goethe's fortune that he was born at the height of Western culture, amidst a mature and satiated spirituality he represented, and that he needed only to be entirely the man of his time to achieve that formal clarity meant when he was later called the Olympian. Nietzsche lived a century later, and in the meantime, a great turn had occurred, which we only understand today. It was his fate to stand beyond the Rococo, in the midst of the complete lack of culture of the 1860s and 1870s. What kind of streets and houses did he have to live in! What manners, clothing, and furniture did he have to see around him! In what forms did social interaction take place at that time; how did people think, write, and feel! Goethe lived in a time full of form; Nietzsche longed for forms irrevocably broken and past; and while one needed only to affirm what he saw and experienced, the other had nothing left but a passionate protest against everything present if he wanted to save within himself what still worked in him as a cultural heritage from his ancestors. Both strove throughout their lives for strict inner form and formality. But the 18th century was itself in form. It had the highest society Western Europe had ever known. The 19th century had neither a noble society nor forms at all. Apart from the incidental customs of a metropolitan upper class, it knew only here and there a painstakingly maintained courtly or bourgeois tradition. And just as Goethe, as an acknowledged member of society, could grasp and solve all the great questions of his time, as taught by "Wilhelm Meister" and the "Elective Affinities," so Nietzsche could only save his task in himself in complete detachment from it. His eerie loneliness stands as a symbol of Goethe's cheerful sociability. One shapes the existing; the other broods over the non-existent - for a dominant form and against a dominant formlessness.

But aside from that, form meant very different things to them. Nietzsche was the only born musician among the great intellectual Germans. All the others were either sculptors or analysts, whether they thought, wrote, or painted. He lived, felt, and thought with his ear. He could hardly use his eyes. His prose is heard, almost sung, not "written." The vowels and cadences are more important than the comparisons. And so, what he felt in the times was their melody, their rhythm. He discovered the key of foreign cultures. No one before him knew anything about the tempo of history. A whole series of his concepts - the Dionysian, the pathos of distance, eternal recurrence - are entirely musical to understand. He felt the rhythm in what one called nobility, custom, heroism, nobility, master morality. He was the first to experience the rhythmic sequence of ages, customs, ways of thinking, races, and great individuals in the historical image that scholarly research had then built up from data and numbers, like a symphony.

And he himself had music in how he walked, spoke, dressed, felt about other people, how he formed problems and drew conclusions. What Bildung was for Goethe was for him rhythm, and in the broadest sense, social, moral, historical, linguistic rhythm, sharpened by deprivation in a time that had little of it. "Tasso" was born from suffering, like "Zarathustra," but Tasso perished in the feeling of his weakness before a present he loved and saw far above himself. Zarathustra despises his present and flees into the distances of the past or future.

This: not being at home in a time, is a German fate. We blossomed too late due to the guilt of our past and then too quickly. From Klopstock and Lessing onwards, we had to traverse a path in barely eighty years for which other nations had centuries. Therefore, it did not come to the formation of an internalized formal tradition and a society of rank as the guardian of this tradition. We adopted forms, motives, tasks, solutions from all sides and fought with them, while others grew up with and in them. Next to the beginning was already the end. Kleist discovered - as the first! - Ibsen traits while still trying to appropriate the characterization of Shakespeare. This tragedy owes German intellectuality a dense sequence of distinct personalities when France and England already had only "writers" - poetry and thought as a profession, not as fate - but also the fragmentary, unresolved, excluding the last goals and roundness.

Today we can encompass the contrast that emerged around 1800 throughout Western Europe - including literary Petersburg - with the words Classicism and Romanticism. Goethe is a classicist to the extent that Nietzsche was a romantic, but that only indicates the predominant color of their being. Each of them also possessed the other possibility in themselves, which sometimes pushed to the forefront; and just as Goethe, whose Faust monologues and West-Eastern Divan are peaks of romantic world feeling, was always striving to master this tendency to the distant and boundless and subordinate it to a clear and strict, traditional form, so Nietzsche placed his acquired inclination to the classical-reasonable, which he was doubly close to as temperament and as a philologist, at least in his evaluations, behind what he called Dionysian. They both stood at the border. Goethe was as much the last classicist as Nietzsche, alongside Wagner, was the last romantic. They both exhausted the circle of these possibilities living and shaping. After them, the meaning of the times could no longer be captured in words and images - as proved by the epigones of classical drama and the followers of Zarathustra and the Nibelungen Ring. But it is also impossible to open up a new way of seeing and saying like them. However strong shapers may emerge in Germany - as individuals and beautiful accidents - even the great line of development is over - they will always stand in the shadow of these two.

It is inherent in Western classicism that it clings entirely to the present under the control of opposing instincts and seeks to dissolve the past and future in it. Goethe's statement about the "demands of the day," his "cheerful presence," means that he absorbed every kind of past, his Greeks, his Renaissance, also "Götz" and "Faust" and "Egmont" into himself to fully incorporate them into the spirit of the present, so that we do not even think of historical foundations with "Tasso" and "Iphigenie." Conversely, distance is the true home of all romantics. They all long for what is far away and foreign from the present, into the past and future of history; none has ever found a deep relationship with what surrounded them.

The Romantic is attracted to what is alien to him, while the Classicist is attracted to what is inherent to him. Noble dreamers and noble conquerors of dreams: some have raved about the conquerors, rebels, and criminals of the past or about ideal states, future realms, and superhumans, while others understood or practiced statecraft as practice and method, like Goethe and Humboldt. The conversation between Egmont and Orange is a masterpiece by Goethe. He loved Napoleon as a figure, seeing him up close. However, he never knew what to do with the men of violence from the past when he had to represent them: his Caesar remained unwritten. Nietzsche, on the other hand, loved just such people only from a distance. Up close—like Bismarck—he could not bear them. Napoleon would have seemed crude, empty, and shallow to him, like the Napoleonic figures who lived around him—the great politicians of Europe and the power figures of the economy, whom he had neither seen nor understood. He needed a great distance between the past and the present to feel related to a reality, and therefore he created the Übermensch and, almost equally freely, the figure of Cesare Borgia. These two tendencies tragically run through recent German history. Bismarck was a classicist in politics. He only calculated with the present, with things he saw and could move, and therefore the patriotic dreamers neither loved nor could understand him until his work was completed and he could be romantically glorified as an almost mythical figure: "the Old Man in the Sachsenwald." But Ludwig II, who perished in his romanticism and never created or could create anything that promised permanence, found this love without respecting it, not only among the people but also among thinkers and artists who could have seen more clearly. Kleist is best felt among us with a shy respect that amounts to a rejection, especially where he managed to overcome the romantic in himself. He stands infinitely distant from most inwardly, in contrast to Nietzsche, whose figure and fate are close to that of the Bavarian king, who is revered even by those who never read him.

Nietzsche's aristocratic taste, lonely and dreamy through and through, is explained by his inclination to distance. The nascent classicism of the 18th century, which arose on the Thames and was then transmitted to the continent, just as Ossianic Romanticism originated from Scotland, is inseparable from the concurrent rationalism. It consciously and thoughtfully shapes, replacing free imagination with knowledge, even with scholarship: the understood Greeks, the understood Renaissance, and therefore finally the understood active contemporary world. These English classicists, all of whom were of rank, helped create liberalism as a worldview, as understood by the 18th century and by Frederick the Great, setting aside differences that one felt confident about in practice, and reasonably dealing with the facts of public opinion, which one could not eliminate or ignore. From the classicism of a noble society emerged English democracy—a superior tactic, not a doctrinaire program. It is based on the long and deep experiences of a class accustomed to dealing with the real and possible, and therefore never in danger of becoming common instead of amiable. Goethe, who was also aware of his social rank, was never an aristocrat in the passionate theoretical sense like Nietzsche, who lacked practical experience up close. In the end, he also never truly understood the power and impotence of the democracy of his time. When he rebelled against herd instincts with the anger of a sensitive soul, it arose from some historical past. He saw, in this unrelenting form, undoubtedly for the first time, how in all great cultures and epochs of the past the masses are nothing, how they suffer history but do not make it, how they are the constant victims and objects of the personal will of individuals and classes born to rule. This was often felt, but until him, this feeling had not destroyed the inherited image of "humanity," whose development seemed like the progressive solution of an ideal task, and whose leaders appeared to be the representatives of this task. Here lies the immense difference between the historiography of a Niebuhr and Ranke, which was also of romantic origin, and his way of viewing history. His gaze, which penetrated the soul of the times and peoples, transcended the mere pragmatic order of facts.

But this gaze required distance. English classicism, which also produced Grote, the first modern historian of the Greeks, a merchant and practical politician, was very much the product of a refined society. They ennobled these Greeks by feeling them as their equals, "presenting" them in the truest sense of the word as cultured, distinguished, intellectually refined people who did everything they did with taste, including Homer and Pindar, whom English classical philology preferred to Horace and Virgil. This classicism penetrated from English society into what corresponded to it in Germany: the small courts, whose princes' educators and preachers were the intermediaries; and the court circle of Weimar was ultimately the world in which Goethe's life became a symbol of cheerful proximity and rounded presence: a sociable house that became the center of intellectual Germany, a fulfillment not visible in any other German poet's life, a harmony of ascent, maturation, and fading, classic in a specifically German sense.

Alongside this path stands another, which also ended in Weimar, starting from the confinement of a Protestant parsonage, from which a large and perhaps the greatest part of German intellectuality originates, to the sun-drenched solitude of Engadin. No other German has lived so passionately as a private individual, apart from everything public and social, although they all have a tendency towards it, even if they are public figures. His dreamy longing for friends was ultimately only his inability to truly live in society, a more spiritual way of being lonely. Instead of the friendly Goethe house on the Frauenplan, there was the small, joyless house in Sils-Maria, the loneliness of the mountains, the loneliness of the sea, and finally the lonely extinction in Turin—the purest romantic life the 19th century has offered us.

Nevertheless, his need to communicate was stronger than he himself believed and certainly much stronger than Goethe's, who, despite all sociability, was one of the most secretive people. His Elective Affinities are a closed book, not to mention the Wanderjahre and the second Faust; his deepest poems are soliloquies. Nietzsche's aphorisms are never such; even the Nachtlied and the Dionysian Dithyrambs are not entirely so. An invisible witness is always present, whose eye rests on him; in this, he remained Protestant and a believer in God. All these Romantics lived in circles and schools. He invented something like this by rewriting his friends into peers or creating a circle of companions in the distant past and future, only to lament his loneliness to them again, like Novalis and Hölderlin. His whole life is filled with the bliss and agony of renunciation, the desire to give himself up and to restrain himself, to attach his life to something that was ultimately not inherent to him. Thus, his gaze developed for the soul of times and cultures, which did not reveal their secrets to a classical, self-assured person.

The works and their order, in which they appeared, explain themselves from the organic pessimism of his existence. We, who are already distant from the flowering years of materialism, should always marvel at what an achievement it was for someone in this age and this state of science in 1870 to write a book like The Birth of Tragedy. The famous formula of Apollo and Dionysus contains much more than the average person even today understands. The most important thing was not that he discovered an inner conflict in "classical" Greece, which for all others, except perhaps Bachofen and Burckhardt, was the purest revelation of the universally human, but that he already possessed the superior view at that time to see into the interior of entire cultures as living individuals. One need only compare it with Mommsen and Curtius. The others understood Greek culture only as a sum of conditions and events within a time and space. The modern way of seeing history owes its origin to Romanticism, not its depth. At that time, it was nothing more than applied philology when dealing with Greeks and Romans and applied archival research when dealing with Western peoples. It developed the view that history begins with written tradition. The liberation came from the spirit of music. From the musician Nietzsche comes the art of empathizing with the style and rhythm of foreign cultures, often in contradiction to the sources—but what does that matter! With the word Dionysus, Nietzsche discovered what excavations finally revealed thirty years later: the underworld and under-soul of ancient culture, and thus the soulful itself behind great history. Historical psychology emerged from historiography. The 18th century and classicism, including Goethe, believed in "the" culture, the one, true, moral-spiritual as the task of the one humanity. Nietzsche speaks from the beginning with the self-evidence of cultures as spectacles of nature, which at some point simply began without task, reason, purpose, or foundation, or whatever the all-too-human interpretations may be. Once—because all these cultures, truths, ways of thinking, and arts belong to a type and form of existence that emerges and then disappears forever—this is stated with such clarity for the first time in this book. That every historical fact is an expression of a soul's movement, that cultures, ages, classes, races have a soul like individual people, was such an enormous step forward in historical deepening that it was not even overlooked by him in its significance at the time.

And yet, it is again part of the Romantic's longing to escape his own nature and the fate of being born in this time that, with his second book Human, All Too Human, he forced himself to serve as a herald of the most blatant realism. These were the years in which Western rationalism ended as a farce, having begun with grandeur under Rousseau, Voltaire, and Lessing. Darwin's theory and the belief in force and matter became the religion of the cities; the soul was considered a chemical process in protein, and the purpose of the world was gathered in a social ethics of enlightened philistines. Nietzsche was utterly alien to these things. He had already expressed his disgust in the first Untimely Meditations, but the scholar in him envied Chamfort and Vauvenargues and their light and somewhat cynical way of dealing with serious matters in the tone of the great world; the artist and enthusiast was embarrassed by the massive sobriety of someone like Dühring, whom he regarded as great. As a thoroughly priestly person, more Christian than his time and more Christian than any church, he set out to expose religion as a prejudice. Now, the purpose of life was knowledge and the goal of history was the development of intelligence. He said this because it pained him, in a mocking form with which he scourged his passion, and with the unfulfillable desire to obtain a seductive image of the future in the midst of the time that contrasted with what was inherent to him.

Although the frenzy of practicality of Darwinism was as far removed from him as possible, he still extracted secrets from it that no true Darwinist suspected. In Dawn and The Gay Science, alongside a way of seeing things that should have been prosaic, even contemptible, there emerges another, shy, reverent one, penetrating deeper than that of any mere realist. Who before him spoke of the soul of a time, a class, a profession, the priest, the hero, the man, the woman, as he did? Who brought the psychology of entire centuries to an almost metaphysical formula? Who, in this history, set forth not the facts or "eternal truths" but the types of heroic, enduring, contemplative, strong, and sick life as the actual substance of events? This was a completely new kind of living forms that only a born musician with a sense of rhythm and melody could find. Now he transcends the physiognomy of historical times, of which he is and will remain the creator, to the horizon of his vision, the great symbols of a future, his future, which he needed to be completely cleansed of the dross of the thinking present, in a sublime moment, the image of the eternal recurrence, as perhaps German mystics in Gothic times had imagined, a circling in the infinite, in the night of immeasurable times, a way of losing one's soul entirely in the mysterious depths of the universe, regardless of whether these things are scientifically justifiable or not. And in the midst of this vision, that of the Übermensch and his proclaimer, Zarathustra, as the embodied meaning of the short-breathed human history of the earthly star on which he himself dwelt, all three figures of a complete remoteness that cannot be related to anything present and which therefore touch every German soul mysteriously. In every German soul, there is a corner where national ideals and dreams of a better humanity sleep. Goethe hardly needed this—therefore, he could not become truly popular. This was what was missed in him, why he was called cold and frivolous. We will never completely free ourselves from this inclination: it represents in us the unlived part of a great past.

At this height, Nietzsche posed the question of the value of the world, which had been ready in him since childhood. With this, the period of Western philosophy, centered on the question of the form of knowledge, was entirely concluded. Here too, there was a classicist and a romantic, or to say it plainly, a social and an aristocratic answer. Life is worth as much as it benefits the whole—that was the answer of the educated English who had learned in Oxford to distinguish between what was presented as an honorable view and what was done in crucial moments as politicians or businessmen. Life is all the more valuable the stronger its instincts are—that was Nietzsche's answer, whose own life was delicate and easily hurt. Nevertheless, because he was far removed from this active life, he understood its secret. That the will to power is stronger than all principles and teachings, that it has always made history and will continue to do so in the future, no matter what may be proven or preached against it, is the ultimate understanding of real history. The conceptual dissection of the "will" is irrelevant to him. The image of the active, creative, destructive will in history is everything to him. The concept has become the aspect. He does not teach; he states. So it was, and so it will be. And even if theoretical and priestly people want otherwise a thousand times, the primal instincts of life will still be the stronger. What a distance between Schopenhauer's worldview and this one! Between Nietzsche's contemporaries with their sentimental world-improvement plans and this acknowledgment of a hard fact. That he succeeded in this places this last Romantic thinker at the forefront of his century. Here we are all his students, whether we want to be or not, whether we know him or not. This view has already quietly conquered the world today. No one writes history anymore without seeing things this way.

And since life was now valued solely based on facts, and the facts taught that the stronger or weaker will to assert oneself makes life valuable or worthless, that kindness and success are almost mutually exclusive, his worldview culminates in a magnificent critique of morality, in which he does not preach a morality but measures the historically arisen moralities by their success, not by some "true" morality. This was indeed the revaluation of all values, and if we know today that he wrongly defined the opposition between master and Christian morality, stemming from his personal suffering in the 1880s, behind this lies the ultimate opposition in human existence, which he sensed and sought and finally believed to have captured in this formula. If we replace master morality with the instinctive life practice of the person determined to act and Christian morality with the theoretical valuation of contemplative natures, we have the tragedy of humanity before us, whose predominant types will always misunderstand, fight, and suffer from each other. Action and thought, reality and ideal, success and redemption, strength and kindness: these are the forces that will never understand each other. But in historical reality, it is not the ideal, goodness, and morality that rule—their kingdom is not of this world!—but decision, energy, presence of mind, practical talent. Complaints and moral judgments do not abolish the fact. Such is humanity, such is life, such is history.

Precisely because all action was so distant to him and he only knew how to think, he understood the underpinnings of action better than any great doer in the world. And the more he understood, the more shyly he withdrew from contact with it. Thus, his Romantic destiny was fulfilled. Under the weight of these last insights, the last part of his life unfolds in the strictest contrast to Goethe's, who was not foreign to action but understood his true vocation as a poet and cheerfully limited himself.

Goethe, the privy councilor and minister, the celebrated center of European intellectual life, could still in his last year of life, in the last act of his Faust, confess that he considered his life fulfilled. "Stay a while, you are so beautiful!"—the word of utmost contentment spoken at the moment when the work of active proximity is completed under Faust's command, to endure from then on—that was the great and concluding symbol of classicism, to which this life was devoted, and which led from the controlled education of the 18th century into the controlled mastery of the 19th.

But distance cannot be created, only proclaimed. And just as Faust's death concluded the classical life path, the spirit of the loneliest of all wanderers now radiates with a final curse on his time in those enigmatic days in Turin, when he saw the last mists dissipate and the farthest peaks clearly outlined in his vision of the world. It is precisely for this reason that Nietzsche's existence exerts a stronger influence on posterity. The fulfillment of Goethe's life also lies in the fact that it concluded something. Countless Germans will revere Goethe, live with him, draw strength from him, but he will not transform them. Nietzsche's influence is transformative because the melody of his vision did not end within himself. Romantic thinking is infinite, sometimes in form, never in thought. It always grasps new areas, consumes them or melts them down. His way of seeing extends to friends and enemies and from them to ever new followers or opponents, and even if one day no one reads the works anymore, this view will last and be creative. Nietzsche's work is not a piece of the past to be enjoyed but a task that demands service. It depends today neither on his writings nor on their contents, and precisely for this reason, it is a German fate. If we do not learn to act as real history intends, in the midst of a time that does not tolerate world-estranged ideals and avenges itself on their authors, in which the harsh action that Nietzsche called Cesare Borgia's alone has value, in which the morality of ideologues and world improvers is more ruthlessly restricted than ever to unnecessary and ineffective talk and writing, then we will cease to exist as a people. Without a wisdom of life that does not console in difficult situations but helps out, we cannot live, and this wisdom appears for the first time in its harshness within German thought with Nietzsche, however much it may be veiled by impressions and ideas from other sources. He showed the most history-hungry people in the world history as it is. His legacy is the task of living history in this way.